I leapt from high-maintenance hair to an all-natural crop—and found a tangle of emotion and politics caught up in all the curls.

Recently my best friend, Heather McGhee—the president of public-policy think tank Demos—met with Chirlane McCray, the first lady of New York City. There was, for Heather and me, a special thrill in seeing the photographs, which showed not one but two powerful women with brown skin—and natural hair.

Heather and I, besties for life, have accompanied each other on our hair journeys: hers from braids to ‘fro to locs, mine from caring to not, and back. Our story has a happy ending—natural hair flowing freely in the halls of power!—but a decidedly more painful beginning.

The daughter of a Nigerian pediatrician and a Ghanaian surgeon, I grew up in Chestnut Hill, a lily-white suburb of Boston. And of all the ways I didn’t fit in—a brown immigrant among blond Americans—nothing caused me more anguish than my hair. My friends tucked their hair behind their ears. They twirled their hair into messy buns. They tossed their ponytails over their shoulders. They let their hair air-dry. Everything that was right and good and effortlessly beautiful was embodied in that simple act: leaving home with wet hair.

I could neither tuck nor twirl. My Afro puff would not be tossed. I couldn’t trust the elements (wind, rain, humidity) to do with my hair as they pleased. All of this I recounted often in adulthood, but laughingly—describing the affliction with the lightness of the healed. It wasn’t until I was asked to write a book of inspirational poems that I recognized my recovery as incomplete.

When Dove approached me to write Love Your Curls, a “poetic tribute to curly hair” aimed at inspiring confidence in girls, I jumped at the chance. Almost all the daughters of my friends—Australian, Cape Verdean, biracial—have curly hair in one form or another. I imagined writing for them: Audriana, Arabella, Angela, Alesha. (Note: These are the children of three different friends. “A” names are having their day.) The greatest challenge I foresaw was finding words to rhyme with “curls.” After “girls,” the options dwindled. Thesaurus in hand, I started to work.

The true challenge presented itself immediately. To inspire the poems, Dove invited women to submit stories online. Reading about a 10-year-old who longed to do the “ear tuck,” I was returned to childhood, to that sense of my worth being tied up in my hair. It’s not that the feeling came rushing back, a memory viscerally experienced. No, the emotion came bubbling up. It had always been there. I was writing a book about loving one’s hair but hadn’t fully made peace with mine. How could a proudly natural-haired woman harbor such angst?

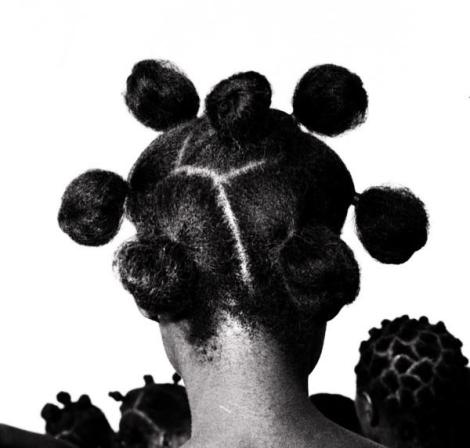

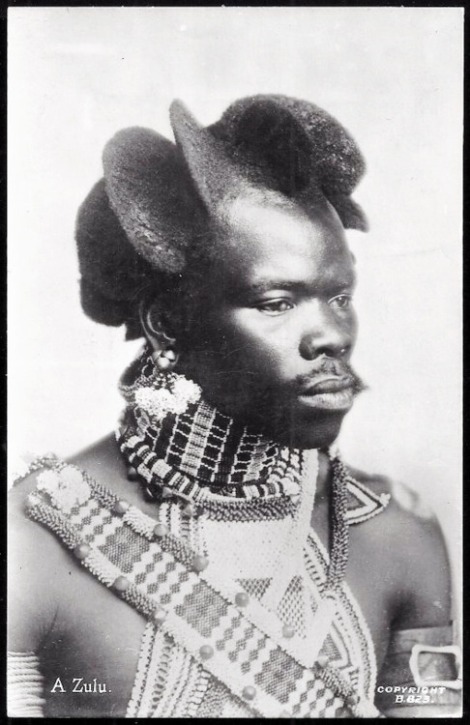

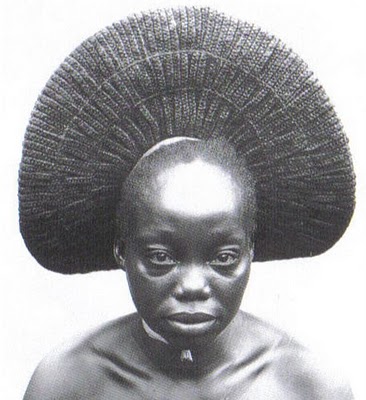

To answer this question, I began to chart the history of natural hair as I’d experienced it personally. All my mother’s photos from the ’70s feature natural hair, often impressively globular Afros. But by the mid-’80s, when I was dreaming of growing up to become Clair Huxtable, relaxed hair was de rigueur. A 2013 BuzzFeed piece explains what changed. During the Martin Luther King-led civil rights movement, one approach to expediting integration was winning over middle-class whites: “[O]ne technique to win their hearts was to look like them…. But by the ’60s, young black activists deemed King’s techniques too slow…. And just as with white hippies, hair length became a way for black youth to rebel…. At the height of its popularity—before [what the writer Noliwe] Rooks called ‘the backlash of the Jheri curl’ during the Reagan ’80s—wearing an Afro became a way of differentiating young black Americans.”

Ah, the Reagan ’80s: home to my young hair discontent. Born too late for the Afro movement and surrounded by blond hair, I begged my mother for a relaxer. But using harsh chemical processors and insisting on swimming sans cap in chlorinated pools left me with problems that Luster’s Pink Oil couldn’t solve. It was only when I started high school that my mother, fearing for my hairline, allowed me to get extensions. In 1993, the year that Janet Jackson popularized box braids in Poetic Justice, I mastered the ear tuck. Braids were like straight hair—they could be tucked, tossed, messy-bunned, air-dried—and I wore them until college. Then the climate shifted again.

Between Erykah Badu’s 1997 debut, Baduizm, and Lauryn Hill’s 1998 Miseducation, the Afros of the ’70s made their comeback. College was all about an Afrocentric aesthetic: head wraps, cowrie shells, two-strand twists. In 2001, when I moved to Brooklyn’s Fort Greene—where Lisa Price (who, coincidentally, worked on the set of The Cosby Show) had launched Carol’s Daughter, her line of natural-hair products—everyone was going natural. It was in many ways empowering, this celebration of diasporic beauty. But I found this movement alienating as well.

The idea was to love oneself, free from external judgment and beauty hierarchies. But new forms of judgment had arisen. There was a certain aspersion cast on women—like my twin sister, a doctor—who continued relaxing. I applauded the rejection of European beauty ideals that diminished brown women’s self-esteem. But to hold that an aesthetic choice necessarily expressed self-loathing seemed dangerously close to judging a book by its cover. And all covers are not created equal. As a February post about Dove’s curly-hair campaign on the blog For Harriet notes: “[B]lack women’s hair…is a wonderful spectrum of kinky and curly combinations. However, those of us with more kink than curl are routinely excluded from movements dealing with natural styling. The praise always goes to the ones with looser textures. We see this on hair care products, advertisements, and even in our own subtle biases.”

This came out months before my Love Your Curls book was released; this author couldn’t have known that I’d include poems expressly written for “kinkier” girls. Still, I took her point. Having survived the effects of mainstream advertising in the ’80s and ’90s, I was disheartened by the “subtle biases” I found within the natural-hair movement of the 2000s. So many women still pegged their worth to how loose or long their hair grew. There were “hair challenges,” “goal lengths”: the language of competition.

By 2005 I’d started wearing weaves almost in protest, determined somehow to opt out of the good-hair hustle. Hairdressers would coo, “But your hair’s so long! You should flaunt it!” Defiant, I’d insist, “Weaves save time. I have books to write.” I loved my Afro but had grown weary of obsessing over—stretching, sealing, twisting, untwisting, finger-combing, fixating on—hair. The idea of “being natural” was for me a proxy for “being free.” It wasn’t just freedom from chemicals and Kanekalon extensions. I wanted to be free from the cliché that a woman’s hair is her glory. I wanted my mind, my heart, and my imagination to be my glory. I didn’t want to be judged by my hair.

And so for years I hid it.

It wasn’t until I sat down to write those poems that it struck me: I’d never truly escaped the Hair Hegemony. The weaves weren’t the problem. I’ll always love weaves: the protection, the convenience. The problem was the premise: that my hair was more fundamental to my beauty than my heart was. As a woman, I aspired to know myself as intrinsically worthy of love, not of envy, admiration, or attention. I longed to feel liberated from all the mandates—silky straight hair! long natural hair! squiggly mixed hair!—with which I’d grown up and to wear my hair however I liked. That was the key. However I liked.

So, a few months back, I cut my hair, side shave and all. I loved it. With my chin-length bob, I received less male attention than with my Farrah Fawcett flips. But the comments I heard were gentle, respectful. I found myself dressing differently, less interested in looking sexy than in being me. I resumed my affair with head wraps. I stopped taking my hair so seriously.

Writing poems about hair helped me to enjoy mine, not as an expression of my worth or a measure of my beauty. When I look at my bestie Heather with Chirlane McCray, I rejoice that our culture has come to recognize their hair as beautiful while knowing that their power, their radiant beauty, comes from elsewhere. This is what I wished to tell my friends’ little daughters: Love your hair because it’s yours, not because it’s you. You are already loved, just the way you are.

By Taiye Selasi | Published in ELLE Magazine August 2015 Edition

Related Posts

Hair Your Way: The Politics of Negro Gals’ Hair

Why Brown Girls Need Brown Dolls

Talking Her Out Of Skin Bleaching Won’t Work

International Blackness vs. Homegrown Negroes

Everyday Racist Treatment of Africans Abroad