As the proudly mixed-race country grapples with its legacy of slavery, affirmative-action race tribunals are measuring skull shape and nose width to determine who counts as disadvantaged.

Brazil has the largest diaspora of Africans outside of Africa, even more than that of the United States of America

PELOTAS, Brazil – Late last year Fernando received news he had dreaded for months: he and 23 of his classmates had been kicked out of college. The expulsion became national news in Brazil. Fernando and his classmates may not have been publicly named (“Fernando,” in fact, is a pseudonym), but they were roundly vilified as a group. The headline run by weekly magazine CartaCapital — “White Students Expelled from University for Defrauding Affirmative Action System” — makes it clear why.

But the headline clashes with how Fernando sees himself. He identifies as pardo, or brown: a mixed-race person with black ancestry. His family has struggled with discrimination ever since his white grandfather married his black grandmother, he told me. “My grandfather was accused of soiling the family blood,” he said, and was subsequently cut out of an inheritance. So when he applied to a prestigious medical program at the Federal University of Pelotas, in the southern tip of Brazil, he took advantage of recent legislation that set aside places for black, brown, and indigenous students across the country’s public institutions.

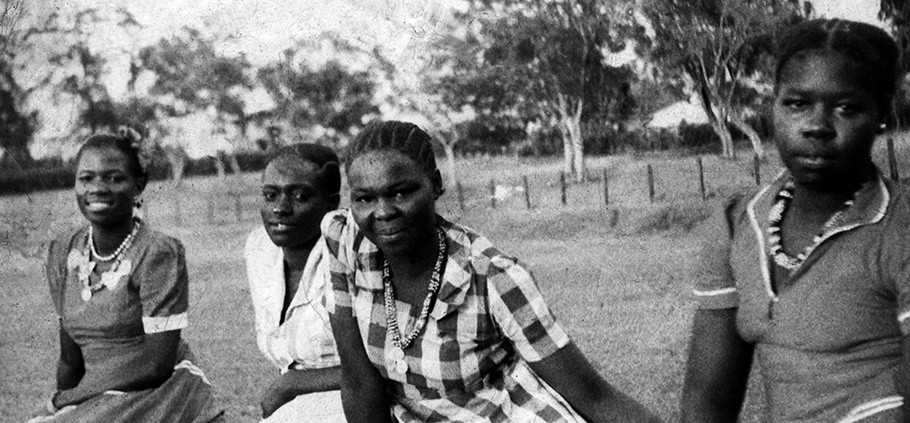

Jongo, a traditional Afro-Brazilian dance always accompanied by the beat of drums, “became pregnant in Angola and was born in Brazil,” according to a traditional jongo chant. When it was first practiced by former slave communities known as quilombos, it was often associated with spiritualism and was exclusively practiced by the community’s elders. Read more about jongo.

While affirmative action policies were introduced to U.S. universities in the 1970s, Brazil didn’t begin experimenting with the concept until 2001, in part because affirmative action collided head-on with a defining feature of Brazilian identity. For much of the twentieth century, intellectual and political leaders promoted the idea that Brazil was a “racial democracy,” whose history favorably contrasted with the state-enforced segregation and violence of Jim Crow America and apartheid South Africa. “Racial democracy,” a term popularized by anthropologists in the 1940s, has long been a source of pride among Brazilians.

As the country’s black activist groups have argued for decades, it is also a myth. Brazil’s horrific history of slavery — 5.5 million Africans were forcibly transported to Brazil, in comparison with the just under 500,000 brought to America — and its present-day legacy demanded legal recognition, they said. And almost two decades ago, these activists started to get their way in the form of race-based quotas at universities.

Salvador, in the northeastern Brazilian state of Bahia has preserved much of its African cultural lineage.

For Brazil’s black activists, however, the breach of the country’s unofficial color-blindness has also been accompanied by suspicion over race fraud: people taking advantage of affirmative action policies never meant for them in the first place.

“These spots are for people who are phenotypically black,” Mailson Santiago, a history major at the Federal University of Pelotas and a member of the student activist group Setorial Negro, told me. “It’s not for people with black grandmothers.”

But in a country as uniquely diverse as Brazil — where 43 percent of citizens identify as mixed-race, and 30 percent of those who think of themselves as white have black ancestors — it’s not immediately clear where the line between races should be drawn, nor who should get to draw it, and using what criteria. These questions have now engulfed college campuses, the public sector, and the courts.

A state of racial vigilance permeated campuses across at least six states in 2016. In February of that year, the student activist group Coletivo Negrada reported 28 allegedly fraudulent students to the Public Prosecutor’s Office in Espirito Santo state. In Bahia alone, students across five universities, including the association of black medical students NegreX, reported on each other for allegedly faking their identity. A few months later, Setorial Negro members in Pelotas took their cue. They filed suit against Fernando and 26 other seemingly white medical students — a process that set an investigation in motion and saw 24 of them kicked off campus in December, earning black activists nationwide their biggest victory of the year. (Three students were cleared of wrongdoing.)

What’s already clear is that affirmative action, as a strategy for racial equality, has proven an uneasy fit for Brazil, resolving certain racial dilemmas by creating entirely new ones.

At least three schools — including Federal University of Pelotas, or UFPel, as the school is commonly known — installed controversial race boards to inspect future affirmative action applicants. Several others are considering doing the same. It is possible that such panels will eventually be codified into law. What’s already clear is that affirmative action, as a strategy for racial equality, has proven an uneasy fit for Brazil, resolving certain racial dilemmas by creating entirely new ones.

“It divided our program,” admits Marlon Deleon, a black second-semester medical student at UFPel who enrolled through the university’s racial quotas system and personally reported on a classmate who did the same, but whom Deleon described as “flagrantly white and blond.”

“A lot of students thought of this as a new inquisition, as a witch hunt,” Deleon said. “But there were many of us who believed it was the right thing to do.”

The United States has provided Brazil with the most direct blueprint for affirmative action. But the two countries’ divergent histories have left them with distinct understandings of race.

Relationships across black-white boundaries have always been rare in the United States. Settlers arrived for the most part in family units, which together with the gaping material and legal chasm between the white ruling class and black enslaved population, ensured that interracial relationships remained taboo. At one point or another, 41 U.S. states had laws banning interracial marriage — 17 of them as recently as 50 years ago. (The Supreme Court finally ruled anti-miscegenation laws unconstitutional that year in the landmark Loving v. Virginia decision.) Meanwhile, race was codified into laws determining that even one drop of African ancestry rendered a person legally black.

Unlike in America, “miscegenation” played an integral role in Brazilian nation-building. White settlers skewed heavily male, and they were vastly outnumbered by people of color. Relationships between white settlers and indigenous, and latter black enslaved women, were not only accepted, but encouraged by colonial authorities (although for the women, they were rarely consensual). By 1872, whites made up only 38 percent of the population.

If interracial relationships were widespread prior to the abolition of slavery in 1888, they became a matter of national duty afterward. That didn’t happen “just because we all happened to get along,” said Mirtes Santos, a law student and Coletivo Negrada member. “It was a way to erase black identity.” Brazil’s government launched a full-on propaganda and policy effort to “whiten” Brazil: It closed the country’s borders to African immigrants, denied black Brazilians the rights to lands inhabited by the descendants of runaway slaves, and subsidized the voyage of millions of German and Italian workers, providing them with citizenship, land grants, and stipends when they arrived.

Today, Brazilians see themselves as falling across a spectrum of skin colors with a dizzying assortment of names: burnt white, brown, dark nut, light nut, black, and copper are a few of the 136 categories that the census department, in a 1976 study, found Brazilians to use for self-identification.

These policies didn’t eliminate race, but they did affect how it came to be classified. The marker of race drifted away from a binary consideration of a person’s ancestry and became increasingly based on one’s appearance. Today, Brazilians see themselves as falling across a spectrum of skin colors with a dizzying assortment of names: burnt white, brown, dark nut, light nut, black, and copper are a few of the 136 categories that the census department, in a 1976 study, found Brazilians to use for self-identification.

What ultimately binds these definitions together is an awareness that the less “black” a person looks, the better — better for securing jobs, better for social mobility. The widespread acceptance of multiracial identities in Brazil coexists with steep racial inequality — a contradiction that the sociologist Edward E. Telles has called “the enigma of Brazilian race relations.” Even the supposed embrace of interracial romance, which is more prevalent among low-income Brazilians, dwindles with each step up the socio-economic ladder. (In comparison, the rate of mixed-race marriages in America increases in proportion to education level, although overall they remain quite rare.) As Brazil’s leading anthropologist told a rapt European audience in 1912, “the mixed-race Brazil of today looks to whiteness as its objective, its way out and its solution.” He predicted that, by 2012, black Brazilians would be extinct.

While 80 percent of the country’s one-percenters are white, Brazilians who look black and mixed-race make up 76 percent of the bottom tenth of income earners. They earn, on average, 41 percent less than their white colleagues. They are also disproportionately represented across the country’s notoriously underfunded public school system. As a result, compared to the mostly white students who can afford a private school education, black and mixed-race Brazilians are less equipped to navigate the college admissions process. Only 13 percent of them between the ages of 18 and 24 are currently enrolled in a university.

Hence the need, so went the argument, for affirmative action. But if the idea seemed justified in theory, it was less clear how exactly Brazil was supposed to put it into practice.

Dancers from a samba school on a float representing African slaves

To tackle inequality in higher education, the federal government passed the Law of Social Quotas in 2012. The law earmarks half of all admissions spots across the country’s federally funded institutions to public high school graduates, regardless of their race. (Public universities, unlike high schools, are more prestigious in Brazil than private ones.) Of those reserved spots, half go to students whose families earn less than 1.5 minimum wage, or about $443 a month. A percentage of the spaces in both categories then gets set aside for black, brown and indigenous students, in proportion to the ratio of white to non-white residents in each given state.

The government gave schools four years, until 2016, to fully comply with the law. The problem is that the law merely asked that candidates report their own race. To many students and professors I spoke with, the only thing that seems to have risen in popular undergraduate programs like law and medicine are the number of white-looking students who gained entry by claiming to be black.

“It’s visible to the naked eye,” said Luana Padilha, a black medical student who enrolled via affirmative action. “By my count, at least 12 of my classmates should have accessed the program through racial quotas. But I look around and can’t recognize any of these people.”

“If you look at a photograph of the incoming medical class of 2015, only one of the students looks black,” said Georgina Lima, a professor and head of UFPel’s Center for Affirmative Action and Diversity. “And he’s not even Brazilian. He’s from Africa.”

The Ethnicity Evaluation Committee, of which Lima is a member, was installed to address this loophole. It interviewed prospective students for the first time ahead of the second semester of 2016. “We saw the most incredible situations unfold,” said Rogerio Reis, an anthropology professor and head of the committee. “People would shave their heads, wear beanies, get a tan. Just a series of strategies to turn themselves black.” Fabio Goncalves, a lawyer and committee member, was about to put one prospective student down as black, when one of his female colleagues, “who knows more about this kind of thing than I do,” told him to note the difference in skin tone between the student’s face and body. The student “had darkened her features with make-up!” he told me, in utter bewilderment.

For as long as black activists have demanded affirmative action, they have also stressed the need for monitoring strategies. “Brazil is the country of frauds,” said Helio Santos, president of the Brazilian Diversity Institute and a leading figure in the black rights movement. “Civil rights efforts that don’t come with any oversight are a joke.” But the recent implementation of verification panels across several schools has raised troubling questions about who gets to define race in a country where people don’t fall neatly into black and white categories.

“My father is black. My official documents say I’m white. I have firsthand experience with miscegenation. This issue is not so clear-cut,” said Kelvin Rodrigues, a second semester medical student at UFPel who is critical of the evaluation committee, even if he supports expelling those who commit blatant racial fraud. Rodrigues looks black, but as someone who graduated from a private high school, he was never eligible for affirmative action spots in the first place.

“If the law stipulates that an applicant’s race should be self-reported, then what right does anyone have to tell that person that they’re lying?” said Luiz Paulo Ferreira, another second-semester medical student. He told me that he considers himself pardo and enrolled in the medical program through the racial quotas, but that he was not one of the 27 students who were investigated.

“How can members of the committee feel particularly qualified to make these judgment calls?” said Ferreira. “And based on what criteria?”

They received strict guidelines from the Public Prosecutors Office: “Phenotypical characteristics are what should be taken into account,” read the instructions. “Arguments concerning the race of one’s ancestors are therefore irrelevant.”

Eleven experts comprised the panel, among them UFPel administrators, anthropologists, and leaders in the wider black community of Pelotas. They received strict guidelines from the Public Prosecutors Office: “Phenotypical characteristics are what should be taken into account,” read the instructions. “Arguments concerning the race of one’s ancestors are therefore irrelevant.”

The official criteria mirrored the way the issue has played out in the public sector as well. In 2014, the federal government approved a law that set aside 20 percent of public sector jobs to people of color. In Aug. 2016, after it had become clear that the law left room for fraud, the government ordered all departments to install verification committees. But it failed to provide the agencies with any guidance.

The Department of Education in Para, Brazil’s blackest state, attempted to fulfill the decree with a checklist, which leaked to the press. Among the criteria to be scored: Is the job candidate’s nose short, wide and flat? How thick are their lips? Are their gums sufficiently purple? What about their lower jaw? Does it protrude forward? Candidates were to be awarded points per item, like “hair type” and “skull shape.” In response to the leaked test, one college professor from the state wrote on Facebook, “We’re going back to the slave trade. During job interviews they’re gonna stick their hands in our mouth to inspect our teeth.”

But black activists say such measures are unavoidable. “A person who does not look phenotypically black is not the one getting killed by police every 23 minutes,” said Santos, the law student and Coletivo Negrada member. “So long as this is how racism manifests itself here, we need to ensure that the people taking up admission spots in universities are the ones with these characteristics.”

The expulsion of the UFPel medical students at the tail-end of 2016, while a major victory for the black activist movement, has not settled the debate around quotas, race frauds, and panels. Seven of the 24 expelled students challenged the university’s decision, and in February, a court gave them permission to go back to class. UFPel has vowed to appeal the ruling. The evaluation committee, meanwhile, has since interviewed candidates for the race quota slots in the first term of 2017. It has also announced a second investigation beyond the medical school, into the more than one thousand students across UFPel that enrolled via affirmative action since the law first went into effect.

The topic has also galvanized conservative politicians, who have enjoyed renewed political power since the impeachment of Brazil’s first female president, Dilma Rousseff, brought an end to 13 years of leftist Workers’ Party rule. Fernando Holiday, a black libertarian activist who spearheaded mass protests against Rousseff, won a council seat during October’s midterm elections on a campaign platform to repeal race quota measures. The far-right Congressman Jair Bolsonaro, who has long expressed vehement opposition to affirmative action laws, has steadily risen in the polls for the 2018 presidential election.

For the time being, individual students will be obliged to navigate the country’s evolving racial codes on their own. Fernando, now expelled from UFPel, remembers his interview with the evaluation committee lasting eight minutes. The panelists started by asking him about when he first recognized himself as pardo. Then, to his surprise, they asked how involved he was with the black activist movement.

“I shouldn’t have to be an activist to be considered black,” said Fernando. Although the Law of Social Quotas is extended to mixed-race candidates, he left the interview feeling like he was being singled out for having light skin. “None of the interviewers were pardo. There was no one there that could identify with me.”