With yet another attack against an African national in India — a Kenyan woman was thrashed in a Greater Noida on 29 March 2017 by unidentified men, an incident that followed close on the heels of Nigerian students being beaten up in an NCR mall — we’re republishing an interview with photographer Mahesh Shantaram, who has trained his lens on the community in India. Shantaram’s quest was to research racism, and he has done this by presenting a series a portraits of African nationals living in India.

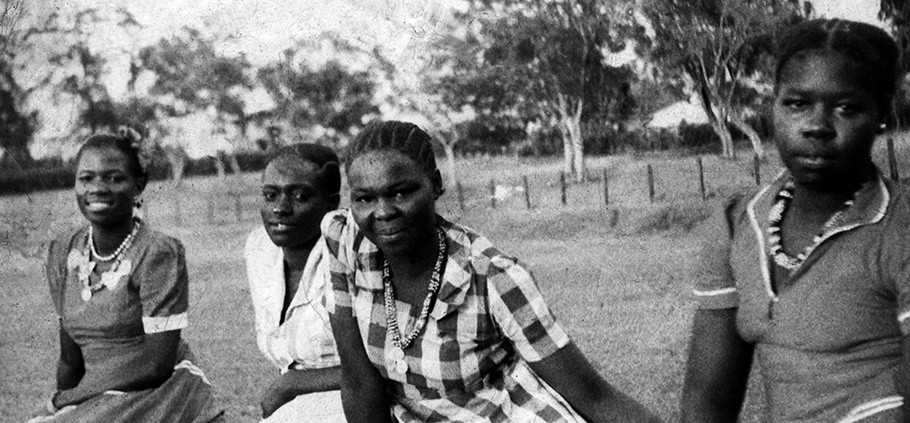

Photographer, Mahesh Shantaram has trained his lens on African students living in India. His objective: to highlight the racism that the community faces. In an exhibition that is now travelling to major Indian cities, Shantaram uncovers the stories of discrimination that these students accept as part of their experiences living here. In this interview with Firstpost, the photographer talks about what inspired him to work on the series:

Mahesh Shantaram. Photo by Trishna Mohan

Most photographers would have opted for a more candid approach to doing this project. Why did you then choose portraits?

You’re right. There are traditional ways of approaching a photo project that wants to look at a community. But what I’m interested in researching is racism, particularly in India. How do you photograph racism? You need something that can act as a visual metaphor or personify it. Anywhere in the world, Africans can tell you a thing or two about racism. That, and the fact that they are visually interesting led me to take the portrait approach to tackle this difficult subject. The project, when exhibited in a gallery, also seeks to put Africans in the consciousness of the Indian public. This is significant in cities like Bengaluru where Africans are practically invisible.

Abdul Kareem from Nigeria, Jaipur 2016. Image © Mahesh Shantaram Courtesy Tasveer

When I was reporting on a similar issue in June, a couple of African students told me that racism was worse in India than Europe. And they were surprised by it. Why do you think that is and why has India made it worse for African students?

Our nationalism is a cataract that clouds our ability to see the real issues facing our society. We are an extremely proud people. Often that pride is misplaced or baseless. For example, we grew up singing ‘Saare jahaan se achha Hindustan hamara…‘ How can we be sure of this? We need to be more self-critical, have an open mind that is accepting of other cultures, and re-evaluate our place in the world of nations. Instead, we are quick to mouth homilies about how India has been a tolerant culture for centuries. In the course of my research, I’ve found that African students’ insecurity in India is due to a cocktail of factors. Some are cultural, such as our legendary aversion to dark skin. Others are socio-economic in nature. For example, in the largely unregulated education industry, colleges play havoc with the future of foreign students. They want African dollars but they don’t necessarily want the Africans!

A majority of these portraits have been clicked at night, or in artificial light. Was that a conscious choice? Are the dark and shadows here, essential elements?

All portraits are and always will be shot at night. (I’m amused by the thought that if I had shot all the portraits by day, nobody would have asked me about that decision!) The problem with daylight is that it describes everything. We see things as they are. At night, I have the power to shape the light in interesting ways and to direct the imagination of the viewer while preserving the mood and mystery of the situation. The mood is dark as is the nature of what we are talking about.

Now that the collection is going to be exhibited (as part of Tasveer’s eleventh season of exhibitions) what do you hope people take away from the exhibition? Could a person who calls these students ‘habshi‘ etc be swayed by the project? Is that the power of the image over the written word that you hope will click with him or her?

I do believe good portraits have the power to make people stop and stare (which anyway is a national pastime) and also become genuinely curious about the life and condition of the subject. Through this project, I hope to put Africans into the Indian public’s consciousness — or is it conscience? But that alone is not enough. The images need to be seen along with the stories to get real conversations going. When I say stories, I mean the big picture that emerges from looking at the connections between anecdotes I’ve collected. This is what I share through my writings. As this show travels across India, it will bring together Indians and Africans in a space of art & culture. Imagine that. So far, Africans meet Indians only in hostile spaces — police stations, TV studios, and hospitals — when there’s an “incident”.

During the project you must have developed a relationship with a lot of the people you photographed. How do they react to your portraits of them and how difficult was it to get them to agree to do this?

Making portraits of vulnerable people and preserving that vulnerability within the image is a challenging task. But if the intention is genuine and the communication is clear, they will readily agree to become collaborators in the process. I think the kind of intimacy that I’ve shared with my subjects comes across in the pictures. I let them know that I’m there to listen and that racism is a shared pain. In a sense, I have the luxury of time that is simply not there in the world of traditional journalism.

What did you learn from this project that is not only limited to photography but also the wider political subject that you are considering here? Is there hope in your mind, that if we humanise issues like you have done, things might change?

For many in the world, the seriousness of the Syrian refugee crisis hit home only when they saw the baby Aylan Kurdi washed ashore. Seeing the human side — rather than the plain political or economic side — of any problem gives us perspective. Six months ago, I started this project not knowing what I was getting into. All I knew was that India has a racism problem, that racism is wrong, and we need to talk more about it. Working on this ongoing project is all about giving flesh to that beast. It’s a pity that people in government and administration are largely clueless about addressing matters of racism. I met up with a diplomat friend — a former Indian high commissioner to Ethiopia — and told him I was working on this project. He said, “The Africans seem to have a lot of complaints lately. Are they really having such a hard time here?” That’s why I need to work on this project and build it up to a crescendo.

Published in FirstPost

Read more: India makes arrests after spate of attacks on Africans

Indian police and onlookers surround African nationals at a shopping mall in Greater Noida on March 27, 2017.

Related Content

Everyday Racist Treatment of Africans Abroad

Brazil’s New Problem With Blackness

Black Women Tackle Dangerous Stereotypes

The Afro-German Experience Under Hitler

Why Brown Girls Need Brown Dolls

Racism’s Big Comeback in America